Feedback sits at the heart of teaching and learning. Everyone agrees on that. Yet giving academic feedback that truly helps students learn is harder than it sounds.

You spend hours writing comments, highlighting issues, offering suggestions, and still… nothing changes. The same misconceptions show up again. The same mistakes repeat. It can feel like you’re talking into the void.

Poor feedback allows misunderstandings to stick around longer than they should. When comments are vague, late, or disconnected from learning goals, students often skim them, glance at the grade, and move on.

In higher education especially, where class sizes are larger and time is tighter, feedback quality often drops under pressure. Efficiency starts to compete with usefulness.

This is where the real challenge lies. Giving feedback isn’t just about saying something helpful. It’s about saying the right thing, at the right time, in a way students can actually use. To do that, it helps to be clear about what academic feedback really is—and what it isn’t.

What Is Academic Feedback (And What It Is Not)?

At its core, academic feedback is information that helps students understand their progress toward specific learning goals. It answers a simple question: How am I doing, and what should I do next?

When feedback works, it narrows the gap between current performance and desired outcomes. It gives direction. It gives purpose.

What feedback is not, however, is just a grade. Letter grades on their own rarely support learning. A “B” or a “72” tells students where they landed, not why they landed there or how to improve. Without comments, grades become endpoints rather than guides. Students receive feedback, technically, but gain very little from it.

Effective feedback also avoids becoming personal. It focuses on the work, not the individual. Comments should point to observable elements in student work—structure, argument, clarity, evidence—rather than traits or assumptions about ability.

That distinction matters more than it seems. Feedback that targets the work keeps students engaged. Feedback that feels personal often shuts them down.

Once this line is clear, the next question naturally follows: if grades aren’t enough, what kind of feedback actually moves learning forward?

Why Effective Feedback Matters More Than Grades Alone

Grades feel official. Definitive. They land with a thud at the end of an assignment and seem to close the loop. But here’s the quiet truth that research keeps circling back to: grades alone don’t teach very much. They summarize performance, yes, but they rarely help students develop the skills needed for what comes next.

Formative feedback, on the other hand, lives inside the learning process. It gives students something to work with while revision is still possible and motivation is still alive. Instead of signaling an ending, it opens a door. Students can see how to improve, not just how they scored. That distinction matters more than most grading systems admit.

Summative feedback has its place. It evaluates final work and supports accountability. But when it stands alone, it often fails to guide future effort. Effective feedback does more than judge. It supports progress, builds confidence, and reinforces the idea that improvement is expected, not optional.

When students receive meaningful feedback that points to specific next steps, they’re more likely to stay engaged, revise thoughtfully, and take ownership of their learning. Grades may record outcomes. Feedback shapes them. And that’s the difference worth leaning into as we move forward.

The Difference Between Formative and Summative Feedback (And When to Use Each)

Not all feedback is meant to do the same job, and treating it as one-size-fits-all is where many courses stumble. Formative and summative feedback serve different purposes, at different moments, for different outcomes. Knowing when to use each is part of giving effective academic feedback.

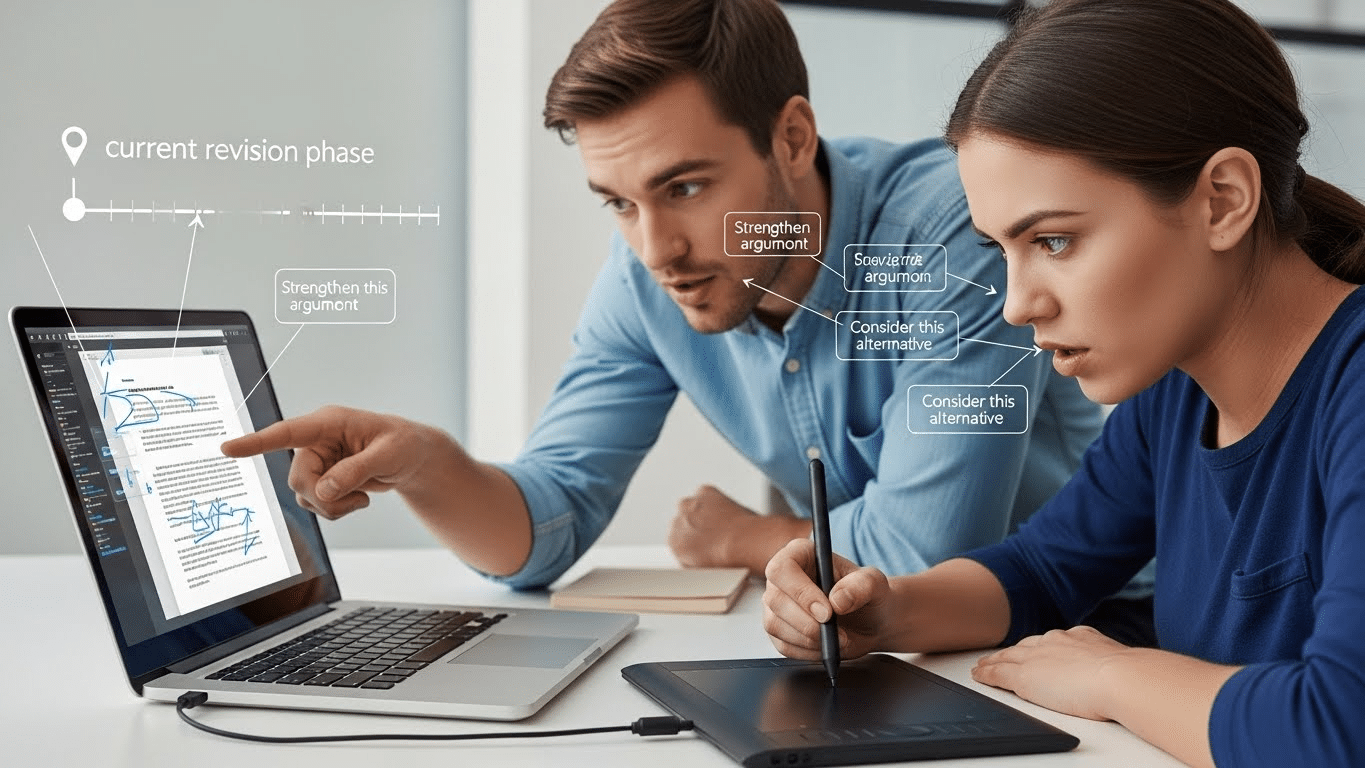

Formative feedback is designed to support learning before an assignment is finished or graded. It’s about guidance, not judgment. Students use it to revise, rethink, and improve while the work is still in motion. This type of feedback is especially powerful for skill development and long-term learning goals.

Summative feedback, by contrast, evaluates final work. It often comes with a grade and answers the question of how well learning objectives were met at the end of a task, unit, or course. It’s useful for accountability and record-keeping, but less effective for growth on its own.

To make the distinction clearer:

- Formative feedback → revision, practice, learning

- Summative feedback → evaluation, grades, accountability

The most effective assessment strategies don’t choose one over the other. They sequence them. Formative feedback guides students forward, and summative feedback marks the milestone when the journey pauses.

When Should Feedback Be Immediate and When Should It Be Delayed?

Timing shapes how feedback is heard. Say the same thing at the wrong moment, and it barely registers. Say it at the right one, and it sticks.

Immediate feedback works best when students are learning new knowledge or skills. Early in the learning process, quick responses help correct misunderstandings before they harden into habits.

When feedback arrives while the task is still fresh, students can connect comments directly to what they were thinking and doing. Engagement stays high. Retention improves.

Delayed feedback has value too, especially when students are applying knowledge rather than acquiring it. Giving learners time to wrestle with ideas, reflect on their choices, or complete a full task can make feedback more meaningful when it finally arrives. In these cases, a short delay encourages deeper processing instead of surface-level correction.

The key is timely feedback, not rushed feedback. Timing should match the learning goal. If the goal is understanding, respond quickly. If the goal is transfer or synthesis, a bit of space can help. Either way, feedback that arrives too late—after the course has moved on—loses much of its power to support learning.

What Makes Feedback Actually Useful to Students?

Students don’t ignore feedback because they’re careless. They ignore it because too often it doesn’t tell them what to do next. Useful feedback closes that gap.

At its best, feedback is specific, actionable, and clearly aligned with learning outcomes. It points to concrete elements in student work and explains why they matter. Vague remarks like “needs more depth” or “unclear argument” rarely help on their own. Students need direction, not just diagnosis.

Clarity matters just as much as tone. When feedback spells out next steps, students are far more likely to act on it. Useful feedback answers three questions: What worked? What didn’t? What should I try next time?

Key features of feedback students can actually use include:

- Actionable feedback that suggests specific changes or strategies

- Targeted feedback linked directly to learning goals or criteria

- Clear next steps students can apply to future work

When feedback does this well, it becomes part of the learning process rather than a postmortem. Students stop seeing comments as criticism and start seeing them as tools.

How to Focus Feedback Without Overwhelming Students

More feedback does not automatically mean better feedback. In fact, too much feedback often has the opposite effect. When students are faced with long lists of comments, margin notes, and tracked changes, they struggle to decide what actually matters.

Research consistently shows that focusing on just two or three key areas for improvement leads to better uptake. This forces you, as the instructor, to prioritize. What will make the biggest difference in the student’s progress right now?

Start with higher-order concerns. Issues like argument clarity, organization, use of evidence, or conceptual understanding deserve attention before lower-order concerns such as grammar or formatting. Fixing commas won’t help if the main idea is still unclear.

In early drafts, minimal feedback can be especially effective. A few targeted comments that steer students in the right direction often produce stronger revisions than exhaustive correction.

Focused feedback does three things well: it respects cognitive load, signals importance, and makes improvement feel achievable. When students know exactly where to focus, they’re far more likely to move forward instead of shutting down.

Using Rubrics to Make Feedback Clear and Consistent

Rubrics do more than justify a grade. Used well, they anchor feedback to learning goals and remove much of the guesswork students struggle with when interpreting comments. Instead of decoding what an instructor meant, students can see exactly how their work aligns with clearly defined criteria.

Rubric-based feedback improves transparency because expectations are shared upfront. Students know what “good” looks like before they submit, not after. That matters, especially in larger classes where grading consistency can drift without a common reference point.

Rubrics also protect instructors from unintentional inconsistency. When every assignment is assessed against the same standards, feedback becomes fairer and easier to scale. Time spent upfront creating rubrics often saves hours later responding to confusion or grade disputes.

Well-designed rubrics support clearer feedback by offering:

- Closely aligned criteria tied directly to learning goals

- Shared expectations that reduce ambiguity for students

- Easier feedback interpretation, since comments map to specific standards

The key is restraint. Rubrics shouldn’t be bloated checklists. Focus on the skills that matter most, and let the rubric guide feedback rather than replace it.

Written, Audio, and In-Person Feedback: What Works Best and When?

There’s no single “best” format for feedback. What works depends on context, timing, and the kind of response students need in that moment.

Written comments remain the backbone of feedback in most courses. They scale well, are easy to reference later, and allow students to review suggestions at their own pace. Marginal notes on written work are especially useful for pointing to specific moments that need attention.

Audio or video feedback brings something different. Tone. Nuance. A sense of presence. Hearing an instructor explain a comment can soften criticism and clarify intent, often in less time than typing everything out.

In-person feedback, when possible, allows dialogue. Students can ask questions, explain decisions, and leave with shared understanding rather than assumptions.

Each mode serves a purpose:

- Written comments and marginal notes for precision and record-keeping

- Audio feedback to convey tone and complex explanations efficiently

- In-person discussions during class time for clarification and connection

Varying feedback modes keeps students engaged and meets different learning needs without overwhelming instructors.

How Peer Feedback Strengthens Learning (and Reduces Instructor Load)

Peer feedback isn’t just a time-saver. When structured well, it’s a learning accelerator.

Giving feedback requires students to articulate standards, identify strengths, and recognize gaps. That process sharpens critical thinking in ways passive receipt never quite does. Students often internalize criteria more deeply when they have to apply them to someone else’s work.

Peer review also spreads responsibility for learning. Instead of feedback flowing in a single direction, it becomes collaborative. Students receive multiple perspectives, and instructors are freed from responding to every draft line by line.

That said, peer feedback only works when it’s guided. Clear prompts, rubrics, and examples are essential. Without structure, comments drift into vague praise or unhelpful criticism.

When done right, peer feedback:

- Enhances critical thinking and evaluation skills

- Helps students learn what quality work looks like

- Reduces instructor overload in larger classes

It’s not a replacement for instructor feedback, but a po

werful complement that benefits everyone involved.

How to Encourage Students to Use the Feedback They Receive

Feedback doesn’t fail because it’s wrong. It fails because students don’t know what to do with it.

To improve uptake, students need explicit opportunities to act on feedback. Reflection alone isn’t enough. Feedback should connect directly to future work so students can apply suggestions while the learning context still matters.

Asking students questions can also shift ownership. Prompts like “What will you revise first?” or “Which comment surprised you?” encourage self-evaluation instead of passive acceptance.

Strategies that improve feedback use include:

- Building revision time into assignments

- Requiring short reflection responses to feedback

- Linking comments to upcoming tasks or projects

When students see feedback as part of an ongoing process, not a final verdict, they’re far more likely to engage with it meaningfully.

Common Feedback Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

Even well-intentioned feedback can miss the mark. Some of the most common mistakes are surprisingly easy to fix once you spot them.

Vagueness tops the list. Comments like “needs clarity” or “expand this” don’t explain how. Over-commenting is another trap. Too many notes dilute priority and overwhelm students. Tone matters too. Feedback that feels judgmental, even unintentionally, can shut down learning.

Watch out for these pitfalls:

- Too many comments competing for attention

- Unclear priorities that leave students guessing what matters most

- Focusing on the student instead of the work, which feels personal rather than constructive

Clear, respectful, focused feedback is far more effective than exhaustive correction. Less, done well, really is more.

How to Give Academic Feedback at Scale Without Losing Quality

Scaling feedback isn’t about shortcuts. It’s about systems.

In larger classes, consistency becomes just as important as depth. Without shared criteria, templates, or structured workflows, feedback quality erodes under time pressure. That’s where intentional design matters.

Rubrics, comment banks, and targeted feedback strategies help instructors provide meaningful guidance without rewriting the same notes dozens of times. Tools can assist with organizing and surfacing patterns, but human judgment still drives what matters most.

High-quality feedback at scale depends on:

- Clear learning goals

- Consistent standards

- Efficient workflows that save time without flattening nuance

When systems support the process, instructors can focus on teaching rather than triage.

How PowerGrader Helps Educators Give Better Academic Feedback

Giving strong feedback consistently is hard, especially when class sizes grow. PowerGrader is designed to support that challenge without replacing instructor judgment.

The platform allows educators to deliver instructor-controlled AI feedback that aligns directly with rubrics and learning goals. Instead of generic comments, feedback stays targeted and relevant to the assignment at hand.

PowerGrader also identifies patterns across student work, helping instructors see where misconceptions cluster or where criteria may need clarification. This makes feedback more strategic, not just reactive.

What sets it apart is the feedback-first, human-in-the-loop design. AI supports scale and consistency, but instructors remain in control of evaluation, tone, and priorities. The result is timely, meaningful feedback that students can actually use—without adding unsustainable workload for educators.

Conclusion:

Feedback isn’t an administrative chore. It’s one of the most powerful teaching tools available.

When feedback is timely, focused, and actionable, students grow. They revise more thoughtfully, reflect more honestly, and build skills that last beyond a single course. Quantity matters far less than clarity.

The most effective feedback systems treat comments as part of an ongoing conversation, not a one-time event. They support progress, not just performance.

As teaching continues to scale, the goal isn’t to give more feedback. It’s to give better feedback—supported by smart systems, guided by human judgment, and centered on learning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How soon should academic feedback be given?

Feedback is most effective when it’s timely. Immediate feedback works best for new skills, while short delays can help with application and reflection.

2. How much feedback is too much?

When feedback overwhelms students, uptake drops. Focusing on two or three key areas for improvement leads to better learning outcomes.

3. Is formative feedback better than grades?

Formative feedback supports learning more effectively than grades alone because it guides revision and improvement before evaluation.

4. What tone should academic feedback use?

A constructive, respectful tone focused on the work—not the student—encourages engagement and reduces defensiveness.

5. Does peer feedback really help students learn?

Yes. Peer feedback strengthens critical thinking and helps students internalize quality standards when it’s structured and guided.

6. Are rubrics necessary for good feedback?

Rubrics improve clarity and consistency by aligning feedback with learning goals, especially in larger classes.

7. How can instructors manage feedback in large classes?

Using rubrics, targeted comments, and tools that support consistent workflows helps instructors scale feedback without losing quality.